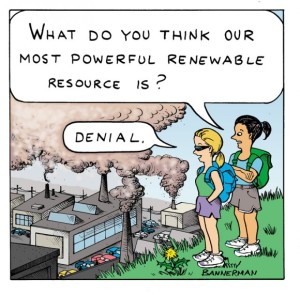

This frame that Mundy builds in his post is an outstanding one for looking at other areas where expert opinions circulate and influence political debates. Broadly, it seems to me that interrogating how expertise functions in multiple contexts is a crucial academic endeavor given the importance of the issues that expert opinions tend to gravitate around. While Mundy focuses on the ramifications of the failure of expert opinion in terrorism and how this has far reaching effects in other arenas, I can see another area where expert opinion works (or doesn’t) in complex and contested ways: the climate change “debates” in the US. (I do hate to use the term “debate” when clearly we are dealing with the very real effects of capitalism and carbon).

What happens if expert opinion—in this case, peer reviewed and verified scientific reports of humankind’s influence on the climate—is ignored, downplayed, insulted, obfuscated, by elected officials? In this case, we long for the “untainted expert” to have a say in what are crucial political decisions for the long-term survival of multiple species on the planet.

As Mundy writes, terrorism must have a “political function” rather than a scientific one if we continue to see “experts” speaking about a concept that is “bankrupt”, or essentially contested. In other words, how can we have experts on an enemy that is everywhere and nowhere depending on the political needs surrounding the definitions? This, as Mundy argues, shows that the “Charlatan profile of the terrorism expert reflects the dubious standing of terrorism as a coherent, uncorrupted idea.”

Can we then tease out what is happening in the use of expert opinion in the politics around climate change denial with Mundy’s formulation? Clearly there is something different happening in my example of expert opinion use (or non-use). What if we replace terrorism with climate change denial from the passage above?

Here goes: Climate change denial must have a political function rather than a scientific one. Just like Mundy’s example of so-called terrorism and oil expertise hiding the politics/antipolitics of our age, the politics/antipolitics of climate change denial is happening prior to expert opinion. Expertise is not allowed in the climate change debate as it would invalidate the very terms of the actual argument: one surrounding the misuse and abuse of earth’s resources for a select few based on a system of profit and rapacious exploitation of the politically weak. Importantly, climate change is not the contested concept, but it is being debated as one by non-expert opinion. Non-expert opinion in control of the very means society has to make substantive changes to our impact on earth’s systems.

Like in terrorism and oil, the crisis in expert climate change opinion and its political denial is one of preserving the productive contradictions between those that profit off the denial of human made climate change–the Anthropocene–and those that are frightened of the consequences of admitting that climate change is “real.” In fact, in another resonance with Mundy’s post, oil and the oil lobby are certainly the power behind keeping climate change from becoming fact.

In the continued struggle of the scientific community to be heard in politics, we can see a positive example of Mundy’s last sentence: “Experts are not above politics nor can they save us from it. But at least they shed light on how power operates.”

We will all feel the effects of climate change–it is too late to change that–but we can mitigate it if we start this very second. Not only do we need to shed light on how power operates we need to disrupt it. Capture it and reflect it back into the eyes of those bent on earth’s destruction for personal profit and gain.

Pingback: 3:1 — Experts Everywhere? Experts Nowhere? — 3 of 3 | Installing (Social) Order

mostly I catch sight of it on PBS’ http://worldchannel.org/

tragically the future is now.

lots of related bits and pieces if you follow my “dmf”

link (next to the whale) back to my more recent blog curating efforts, state governments (as well as bridges and such) are falling all around us as I type, the end I think of the post-WW2 bubble.

LikeLike

Interesting, dmf. Where do you see such a future being imagined in popular culture? Is “The Walking Dead” too extreme?

“Snowpiercer” does an amazing job of visualizing the revolutionary predicament we face. Unfortunately, I think “Children of Men” hit it on the head: large sacrifice zones across the globe in which an archipelago of elite safe havens emerge.

LikeLike

or about how to survive the collapses without being reduced to a creature of “bare” life and than make one’s way in the ruins…

LikeLike

What is the main snag? Methinks 2+3. Perhaps it’s related to the nostalgia I was commenting on or the power of Mertonian norms. We yearn for science to save us and yet scientists are afraid that their credibility will be tarnished if they descend into politics. (Contrast this with the terrorism expert who lives to be on TV, speak to congress, or get a fat CIA/DOD contract.) The more that the pro-carbon lobbies pour into obfuscating the science, the more scientists retreat from politics because they — like us — see politics as a place that corrupts science. Mertonian ideology is thus very susceptible to being used to maintain anti-democratic relations of power.

On the idea of revolutionary experts, I’m skeptical as always. It brings me back to the Chomsky-Foucault debate, in which Chomsky lays out a rational plan for social libertarian revolution but then Foucault suggests that we need much better understandings of power to avoid the tyrannical fate of all previous revolutions. Foucault’s concern has since become the de facto mission statement of — for lack of better terms — post-Marxist, post-structural, and post-colonial academia. How’s that research coming along, people?

The funny thing about power is its ability to be easily interrupted for short periods but the difficulty of managing it democratically over the long run. If Chennoweth’s data is right, it takes only a small percentage of a country’s population to achieve a revolution (I believe it’s only 5-10%, maybe less). One does not need a PhD in mechanical engineering to make a car stop working but to keep it running is another thing. The trick might be in determining what needs to be monkey-wrenched (permanently disabled) and what needs to be reformed. Given that we live in the over-developed world, there’s a lot that can be abandoned without *necessarily* impacting people’s ability to live with freedom and dignity. The problem, as Klein notes, is that such sustainable de-development is being held hostage by capitalism’s irrational growth imperative, an imperative to which the world’s most influential social science (economics) and power governments are slavishly obedient.

If you believe Homer-Dixon, we will experience de-development whether we like it or not, so best to do it in a planned way. Since the term “planned” scares the crap out of me (thanks, “Seeing like a state”), it might be a matter of opening conversations on what just and democratic de-development should look like. It’s fundamentally a conversation about a radical re-distribution of power and the kind of regime that can sustainably manage it. In this sense, I guess it has to be a conversation about revolution.

LikeLike

ah yeah well that’s part of why I shifted from ANTHEM to syn-zero-ing

LikeLike

I was a student activist in those days organizing teach-ins, fund-raising, networking, pushing divestment, protesting the CIA and school of the americas, and I really thought that if the American people had to face what the CIA/NSA/DEA/military was up to they wouldn’t stand for it, how wrong I was…

LikeLike

ah yeah, as I see it the thing with climate-change is we don’t have much time left so if we don’t at least slow it down significantly in the near-term than it doesn’t matter what long-term plans we may generate for alternative forms of governance/exchange short of some variety or another of madmaxing it (see the latest news from the failing state of yer choice to see how that all plays out).

On a perhaps more immediate matter for this crowd if consciousness-raising isn’t making the social/political connections needed to shape the way things get done in the places that matter and can’t create significant public uprisings than is this all playing while the ship goes down, whistling thru the graveyard, etc?

LikeLike

Seeing politics as an alternative to corporate entities seems less possible now than any time in my recent memory…

LikeLiked by 1 person

http://bloggingheads.tv/videos/33341

who needs (academic) experts?

LikeLike

An answer from Michael Hardt….

LikeLike

well or at least jam the flows, make it too costly and such.

not sure if we have any real clue about how to reorganize, among other things serious questions remain i think about the role of experts in democracies and other related challenges of making things public:

http://faculty.cas.usf.edu/sturner5/Papers/ExpertsPapers/paper.htm

LikeLike

Good old fashioned revolution? Throw off the oligarchs?

LikeLike

here is stef’s colleague jodi dean who in other arenas has rightly argued that given the scale of the operations & problems we are facing we need a massive political party to respond in kind (in terms of effects/powers if not in tactics/means) acting in the face of local extraction/pollution:

http://jdeanicite.typepad.com/i_cite/2015/02/clear-message-about-300-descend-on-geneva-for-a-rally-march-in-support-of-seneca-lake-finger-lakes-times-news.html

not a party in sight that i can see.

LikeLike

What is the main snag then?

1. Are scientists unconvinced by their studies to stand behind them as a citizen as well as a scholar?

2. Are scientists, in contrast, convinced by their studies but also convinced that if they do speak out that they will be targeted by politicians?

3. Do scholars suck at politics?

4. Or, as DMF suggests, do we now need experts about how to create a global green network of committed monkey-wrenchers? (provided we are confident in the research)

Thoughts?

LikeLike

ok but where is the new means to organize a massive and sustainable counter-effort supposed to come from?

we know where to go if we need a letter to the editors written:

http://www.theguardian.com/education/2015/feb/02/counter-terrorism-security-bill-threat-freedom-of-speech-universities

but an international green-party and monkey-wrenching network, not so much.

LikeLike

Lots of interesting things going on here. My main point was to say that there is a kind of Rand-ianism lurking behind insinuations that politics is suppressing expertise. And, most interestingly, it comes from the Left. To me, this is antipolitical because there’s this nostalgia for a world in which key decisions are taken out of the hands of bad politicians and given to good experts.

The politics of climate change denial is an interesting alternative example because it’s so blatantly obvious what’s going on. We see expertise being very explicitly obfuscated by an overt agenda, funded by the oil industry, to sew confusion and doubt among the public and politicians. None of this is secret; we have the documents and we know who the key players are and the dollar amounts being spent. But at this point in climate change, the issue is entirely political. It is a matter of people organizing for change (as Klein suggests). Hoping that one more scientific report will change things is suicidal, and so I’m even more frightened by the antipolitics in our veneration of experts and dislike for governing.

What we also need are scientists being less scientific and a bit more political. Such a revolt will have to be on a scale never seen, whether in the anti-nuclear movement among atomic scientists or the “concerned” scholars movements against the Vietnam War and Apartheid.

LikeLike

lots of work out there on how this issue plays out in terms of the politics/economics but next to none that I’ve seen in relation to “we need to disrupt it”, and this is all too often the “merely” in academic studies the question of how to get meaningful things done in the public/political realm.

Latour for example declares “war” on climate deniers/polluters and than launches a stage-play…

https://www.youtube.com/user/situatingscience/videos

LikeLiked by 1 person