This is an excerpt from a paper that we will present in Izmir, Turkey, next week as part of the European Workshops in International Studies; we are in the social theory section (big surprise) organized by Benjamin Herborth, University of Groningen, and Kai Koddenbrock, University of Duisburg-Essen.

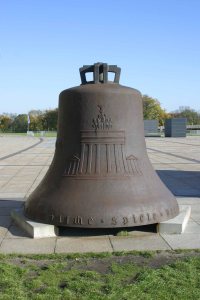

(left-over Nazi bell from the ’36 Summer Olympics)

On the failures of constructivist language for our purposes.

In each case, the materiality of the object contributed to its fate. There were clear economic, cultural, and logistic costs and considerations associated with our objects under study being de-constructed, re-constructed, or, for lack of a better term, un-de-constructed, or, put simply, left. Upon even modest reflection, the available constructivist vocabulary seems to fail us in these moments; primarily developed for understanding how things are to be built, we find it difficult to utilize such language for encapsulating and illuminating the processes associated with the allowable decay resistant materials and the slow unintended or unattended-to wasting-away of durable objects.

The only apparent option is to capture attempts at (re)framing — discursively, symbolically, but not practically — the (re)appropriation of monuments in official and unofficial accounts of history. People “make sense” of these ruins, so the classic constructivist interpretation goes. And as soon as they stop or do not care any more there is nothing left to say. That is exactly what Foucault bemoaned when he complained about a historiography that turns monuments into documents. One can easily see that his complaint does not only hold for historical accounts, but for social sciences looking at contemporary issues as well: if we cannot find someone who makes sense of something, then that something simply does not count. But as our cases show: that does not make these massive pieces of concrete, bronze, and iron go away; it does not even leave them untouched. Even when people do not care, forget, or even ignore: the stuff left-over by former state projects stays and shapes what can and cannot be done with it.

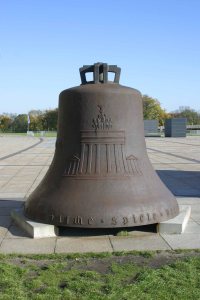

(Soviet War Memorial)

As we view the cases, those Soviet War Memorials constitute a kind of classic form of international relations, one held together by international treatise and inter-governmental agreements regarding the conditions of maintenance for the sites. Based on agreements, the materiality of the sites are not to be marred. The formerly-Nazi Olympic bell constitutes another form of international relations that is de facto, meaning, the bell’s unearthing and repositioning outside the Olympic stadium is not the outcome of treaties with another nation or the result of any linger agreement from former German governments. The bell’s durable material hardly needs to be willfully maintained; however, to remove it would require a considerable quantity of will, both economic and cultural. As the international stage observes how Germany will learn to deal with its past, the irremovable bell lingers-on in public view with only modest material transformation, which recognizes without celebrating the past. How Germany relates to the material residues of past governments becomes a form of international relations.

(perpetually graffitied Ernst Thälmann Park memorial bust)

The Thälmann bust appears to us as an example of international relations unquestionably shaped by materiality, or, put another way, as a standing example of material international relations. The costliness of its decommissioning outweighed so greatly the will and coffers of the Berlin city commission that, despite being selected for removal on the basis of historical value, the monument endures (Ladd,1997: 201). Unlike the Soviet War Memorials, the the Thälmann bust is not vigorously maintained; however, it has also not been disabled like the Berlin Olympic bell. The operant or public identity of the memorial in Ernst Thälmann Park is one of a graffitied material behemoth. Creative urban artists embellish the statue and only occasionally and without ceremony is hulk washed of the ongoing alterations that it is subjected to from the public.

In sum, the Soviet War Memorials endure for classical reasons of international relations; the Olympic bell endures, irremovable but intentionally altered so that it no longer bears the inscription of a past government and it is incapable of expressing its material purpose to ring; though its removal was approved by a commission whose sole purpose for convening was to determine how the Berlin cityscape would be selectively altered, through its hulking materiality the Thälmann bust endures in a state of semi-permanent but allowable vandalization.

As we reflect on the monuments to a former age, we think of commentary on the repurposing of the Berlin Olympic stadium. Walter’s (2006: xiii) reflects in an extended passage from a perhaps little-read preface:

“Whereas other Nazi edifices such as the rally grounds at Nuremberg are rightly abandoned, this is a building still very much in use – even playing host to the 2006 World Cup final. Although some argue that a structure so closely associated with the Nazi period should not be used, it would seem churlish (and uneconomical) to abandon so handsome and vast a building. In 1936 it may well have been regarded as an architectural embodiment of the waxing power of the new German Reich, but in 2006, the seventieth anniversary of the Nazi’s Olympics, it stands as a symbol that Germany has the ability to come to terms with its past. Why should it not be used? What harm does it do? The shape of the Olympic Stadium does not register as a symbol of evil in the same way as the infamous entrance to Auschwitz, with its railway lines converging to pass under its all-seeing watchtower. The stadium may well not be free from guilt, but like many associated with the Nazi regime, it does not necessarily deserve the death penalty.”

The language used in the passage above to execute an old stadium produces a clear image in the mind; however, do not mistake it as a heartfelt call from the inner-circles of STS to adopt a relational materialist approach to the symmetrical depiction of humans and nonhumans. Still, there is a kernel of insight worth coaxing into germination.

Sentencing a stadium to death would not only be deemed mean-spirited and irrational by Walters, the implication is that one way to deal with international relations (even with old dead states, like the Nazi state) is through the material relations — what Barry calls “material politics” — of monumental spaces such as architect Werner March’s, on Hitler’s orders, grand Olympiastadion staged in the Reichssportfeld (which was built on the foundation of the previous Olympiastadion from the aborted 1916 Games in Berlin). By material politics, Barry conceptualizes processes by which the material world gets drawn into a dynamic relationship with politics; the material world, as it happens, is an important resource for the practical conduct of politics. In STS, Barry’s approach can be contra-positioned with the old adage that “artefacts have politics,” by which Winner (1986) means that technologies have politics as a quintessential part of their design or contextual situatedness.

Returning to our main line of discussion, Barry’s project is explicitly about dealing with a project under construction, in his case, laying a rather large oil pipeline, while our is about dealing with a project long-since constructed. Barry’s case is emergent; our cases are left-over. For us, this sometimes means intervention or decommission and other times it means preservation or transformation, either way, the state must relate to these residues of past states. While the constructivist language common to STS accounts serves Barry well, we find it wanting and search for alternatives more suitable for conceptualizing and describing decay amid durability and the state of being left behind.

You must be logged in to post a comment.