In 2015, Andy Borowitz wrote a piece for the New Yorker on the dismal state of American infrastructure in light of a mandate to build a “giant” wall.

In 2015, Andy Borowitz wrote a piece for the New Yorker on the dismal state of American infrastructure in light of a mandate to build a “giant” wall.

Great video worth the time to listen (about 30 mins) about the history of “public works” in the US and around the world, and the term’s gradual replacement with “infrastructure.”

https://www.stitcher.com/podcast/ft-alphachat/e/58800747?autoplay=true

Thanks, dmf, for finding it!

In the final post of the three part post (here are two and one), I take-on “futuring” as a way to know the future of the future.

We make futures to increase our influence on our networks in ways that are perceived beneficial. Futuring involves creating information about the future by extrapolating the patterns, anticipating outcomes by contemplating future states of affairs, and leveraging this to generate insight to inform action.

In a world with where most of the inhabitants on this planet who struggle to foresee alternative pathways to procure their the next meal, we are reminded of the privilege it is to do futuring. Most of the advanced tools of futures studies and foresight today were developed in the think-tanks supported by the defense industry. Its a diverse toolbox of quantitative and qualitative methods, that continue to be blended and sequenced in novel ways for different purposes and questions-at a high price.

My expectation is that the future of futures will be an expansion of access to futuring for more people, that affords many more to undertake informed action. The costs, technologies, information, and time necessary to wielding advanced planning and foresight tools are becoming more accessible.

I share the concerns with the previous poster’s concerns with algorithms – the best chess player used to be the human. Then it was a machine. Now it is a machine-supported human. Most routine manufacturing is done by already human-supported machines. In “lights-out” factories, complete automation allows for operate without human intervention – no lights, no heat, no toilets. The orders come in, widgets are manufactured or printed according to specification, boxed, and shipped out. The robots inside are doing things, but are unable to make non-routine plans in futures with humans in them.

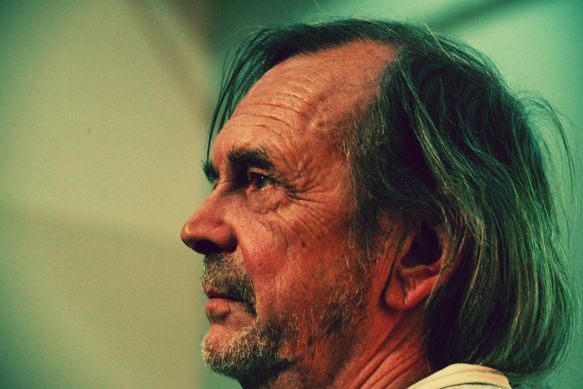

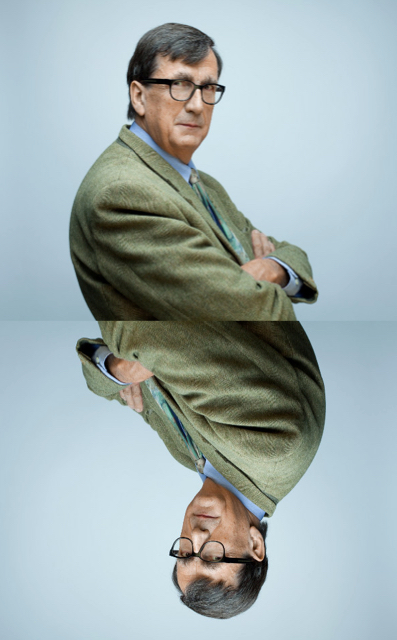

Erik Olin Wright passes away (New York Times article):

Erik Olin Wright, a Marxist sociologist who helped bring to light the complexities of social and economic classes and explored alternatives to capitalism, including a universal basic income, died on Jan. 23 in Milwaukee. He was 71.

One of his earliest books, “Class, Crisis, and the State” was a game-changer for me.

* image source: https://www.ssc.wisc.edu/~wright/

After Jan‘s post earlier this week, I was moved by a comments to it, namely, the idea that it is, in fact, so difficult to talk about the future of the future, and, in particular, the good comment that “aren’t we always making the future?” I plain sense, I do think that we are always “making the future” in the process of doing just about anything; however, taken to its not-too-distant logical conclusion, this would mean that “making the future” is so obviously ubiquitous that it cannot — in and of itself — be special.

I confess, that did not encourage me much.

It is the latter, not the former, that moves me, and to which I devote the next couple of paragraphs. It is from this vantage point that “the future of the future” might productively be discussed.

When we came up with the idea to restart the 3-1 series with a collection of posts on “the future of …[FILL IN THE BLANKS]”, my initial thought was to end this collection – much later this year – with a post on “the future of … futures”. I told Nicholas about that and his answer his reaction was as hilarious as fitting: While a last post on that would be the obvious and reflexive thing to do, opening up with it would be even better as it sets the stage for whatever will follow. So here I am, time is up, “2 minutes left and 10 slides to go”: The future of … futures!

Blog, I am back!

I would like to invite you to read my, Andrzej Nowak‘s, new article The Burden of Choice, the Complexity of the World and Its Reduction: The Game of Go/Weiqi as a Practice of “Empirical Metaphysics”, where actor-network theory meets with game of Go/Weqi, with little help of Mao Zedong.

As noted in a previous post, we are doing a redux of the 3:1 series, based on our past 3:1 series and the 3:1 concept, for the year devoted to “The Future of [Fill-in the blank],” wherein we will discuss various topics of relevance through the lens of the future.

After the Futures and Foresight Conference in Warwick in December, three members from the Association of Professional Futurists (APF), Andrew Curry, Wendy Schultz, and Tanja Hichert, sat down and recollected their takeaways and highlights from the conference and recorded it as a podcast. As the first in an occasional series of “Compass” podcasts, we were honored that Matt’s presentation was able to generate some laughter from them (you will find their recap of Matt’s talk at 15:30 about our work in this paper, this one, and this one). Perhaps readers of Installing Order would like to contribute some podcast material in the future (!?) — we would be happy to put it on the blog.

The blog is making some big changes in 2019:

Cheers and Happy New Year!

* image from: http://www.walkwithgod.org/where-am-i-going/

Oldy but goody.

Proverbial “Door to Hell”, Derweze, Turkmenistan: Check out a video here.

The Door to Hell is a natural gas field in Derweze (also spelled Darvaza, meaning “gate”), Ahal Province, Turkmenistan. The Door to Hell is noted for its natural gas fire which has been burning continuously since it was lit by Soviet petrochemical scientists in 1971, fed by the rich natural gas deposits in the area. The pungent smell of burning sulfur pervades the area for some distance (Wiki).

Not the first time we talked about disasters on the blog. For example, about how Google worked in Japan post-Fukushima disaster to use Google-cars to help find missing persons. About how the intersection of infrastructure studies and disaster studies will likely grow in future years. More recently, we featured “Philip Mirowski’s Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste … an…

View original post 15 more words

This is the kick-off to a new and improved section of the existing blog, the “Teaching STS” section, which is just been transformed to the “Teaching STS/FS” section, and each new and old post in this section will be differentiated with a “Teaching STS” or “Teaching FS” in the title to help sort things out.

This image above comes from “plan59” and was found through a great blog, “paleofuture” (similar cool stuff on pintrest too). In the past, we’ve used this image, which is closer to the year 1900 than it is to present day, as a teaching tool.

Matthew Spaniol and Nicholas Rowland just presented a paper, “Intersecting Futures Studies and STS” at the Futures & Foresight Conference in Warwick 10-11 December (presentation here). The conference was only the second of its kind in the last decade. There were 80 participants, double over the 2015 conference. This year it had expanded for just Scenario Planning to include Foresight.

My colleague, long-time collaborator, and now co-blogger, Matthew Spaniol, just released a video about our recent paper that free and available here. The video is called “Defining Scenario” and is available in a short, quick version (here) and a detailed, extended version (here).

Available here and also Review_of_Capitalization (from S&TS in 2017).

* image from: https://www.ibmbigdatahub.com/blog/turning-time-money-forecasting-production-costs

The field of futures and foresight science (FFS) has problems that science and technology studies (STS) can help to understand. Based on recent publications, insights from STS have the potential to shed new light on seemingly intractable problems that inevitably come with the scientific study of the future. Questions like: What is a scenario?

Consider this quote from a prominent scholar in the field:

Short piece pointing to research on embracing values in science in a period of ‘post-truth’ public discussion.

Help us with our “Reading List” — what should we add or subtract?

Planning practices — strategic planning, scenario planning, and the like — have taken firm root in both the public and private sector. Governments roll-out security scenarios. For-profit firms establish short-term, medium-term, and long-term strategic plans. More and more; on and on, the planning seems never to stop in our postmodern age.

Most folks are, thus, rightly surprised to find out that scholars typically do not know why planning processes work or, when they fail, why. The reasons are deep-seated and my co-author (Matthew Spaniol) and I (Nicholas Rowland) tackle a few of them in our new paper “the scenario planning paradox,” which builds on some of our previous work about multiplicitous notions of “the future” and plural “futures” as well as the social practices associated with the process of scenario planning in the first place. Below is the abstract and link to the planning paradox paper:

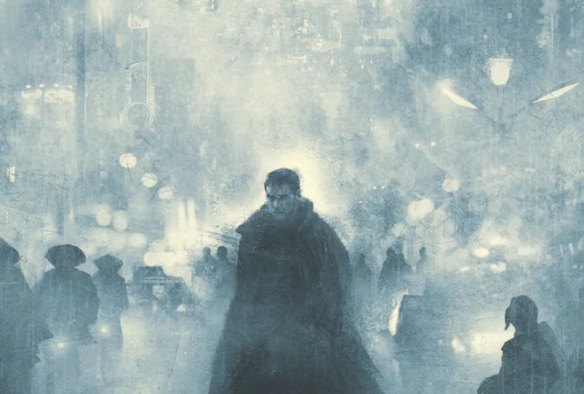

“‘Blade Runner’s’ chillingly prescient vision of the future” offers a (brief) review of the 1982 Ridley Scott film and how much 2017 appears to reflect Scott’s portrayal of the human-machine interface. With ‘Blade Runner 2049‘ coming out soon (today, I think), the short piece is a nice opportunity to return to the 1982 now-classic film.

As a sidebar: In terms of visions of the future, it is always interesting to me that “vision of the future” is characterized here as “look, Scott got it more right than he might have known;” however, his view of the future, a strict prognostication or even foresight, is not really consistent with the academic study of the future (not that the author of this piece should be held to that standard). On balance, there are “ethnographers of the future” looking into science fiction too, but there is also a growing linkage between STS and a small world called futures studies, ontological research on the character of the future as a concept, and even scholars that do not owe much of their intellectual heritage to either tradition making serious headway into managing multiple futures. Getting past “visions of the future made in the past were right or wrong” as a framework might make for some interesting discussion in the public media realm, provided readers want something past the all-too-easy “they got it right!” or “ha! They botched it” critiques leveled safely from the sidelines in retrospect.

It is bad to demand the retraction non-fraudulent papers. But why? I think the argument rests on three intuitions. First, there is a legal reason. When an editor and publisher accept a paper, they enter into a legal contract. The authors produces the paper and the publisher agrees to publish. To rescind publication of a […]

Dovetails with concerns over peer review in general, related horror stories, and even the outer limits of the practice.

via why is it bad to retract non-fraudulent and non-erroneous papers? — orgtheory.net

* image from here.

25 years after Andrew Pickering’s “Science as Practice and Culture”* was published, it was just reviewed. Helen Verran (History and Philosophy of Science, University of Melbourne) just wrote a retrospective on the book that is worth the time to read and, even better, it is free to one and all: https://sciencetechnologystudies.journal.fi/article/view/65250

* Casper Bruun Jensen noticed on Twitter that I wrote “Mangle of Practice” in the previous version of this post rather than “Science as Practice and Culture.” I guess I was showing my cards there in terms of preference.

Just out: “Mapping “the ANT multiple”: A comparative, critical and reflexive analysis” by University of Sussex Science Policy Research Unit Brighton UK; University of Tartu Institute of Social Studies Tartu Estonia) in The Theory of Social Behavior.

AbstractDespite decades of development, Actor‐Network Theory(ANT) continues to be characterized by a good deal ofambiguities and internal tensions. This situation hasled to a suggestion that instead of one ANT it may bemeaningful to speak of ‘the ANT multiple’. Followingthis line of reasoning, this article aims to create a mapof the variety of positions riding under the ANT banner.Based on an in‐depth reading of ANT literature, sevendifferent interpretations of ANT are identified and sub-jected to critical analysis; it also accommodates for theconcerns of ANT proponents about the way ANT hasbeen previously criticized. The results of the analysisserve to increase the reflexivity of both sides of thedebate about their underlying assumptions, and providesuggestions how ANT could be employed, developedand criticized more productively in the future.

See this terrific review of the interesting book, and there is a free introductory chapter for those interested:

*image: http://www.bioethics.com/medical-tourism

Jennifer Terry, Attachments to War: biomedical logics and violence in twenty-first century America, looks into the nexus of war, medical treatment, and prosthetics — looks promising.

And in lockstep with my last post and my continuing interest in the prosthetics of military violence… A new book from Jennifer Terry, Attachments to War: biomedical logics and violence in twenty-first century America, also due from Duke University Press in November: In Attachments to War Jennifer Terry traces how biomedical logics entangle Americans […]

Another, in a long line of discussions, about how postmodernism is to blame for our ills. Please bask in the reflected glory of a few scholars to reshape the world from their desks. It is truly amazing.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-unfortunate-fallout-of-campus-postmodernism/

For other reading about postmodernism that is a little less bombastic, see postmodernism 1, 2, and 3.

Actor-Network Terminology Blog:

Welcome to WordPress.com. This is your first post. Edit or delete it and start blogging!

There is a paradox in clinical uncertainty management. While contemporary medical education and training dismisses prognosis in favor of diagnostic and treatment skills, prognosis is ever present in daily medical life. In fact, physicians arguably engage in more prognostic behavior than most other professionals because, bound by their duty to heal, they are routinely called upon to concurrently navigate short-term and long-term care goals. With new accumulating evidence establishing prospection (i.e., the mental simulation of possible futures) as a central organizing principle of cognition and behavior, and with more clinicians warning about the central role of prognosis in clinical decision making, concerns about the relative neglect of prognostic training are becoming louder. Yet, although there is much writing and some fairly robust guidelines about how physicians should do prognosis, very little is currently known about what the process of medical prognosis actually looks like on the ground. I begin to fill this gap in my forthcoming book How Doctors Make Decisions, based on a three-year ethnographic study of hospital cardiology.

With a trillion-ton iceberg cleaving from Antartica, and debate over the exact causes seems never to end, I wonder “what is the infrastructural equivalent of it?”

One immediate answer is found the giant, offshore seed vault Svalbard (Norway), which was colorfully referred to as one of the “Arks of the Apocalypse” in the New York Times Magazine. The anthropocene stirs, no matter what the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) suggests, and seed banks are a fascinating reflection of this transition for so many reasons.

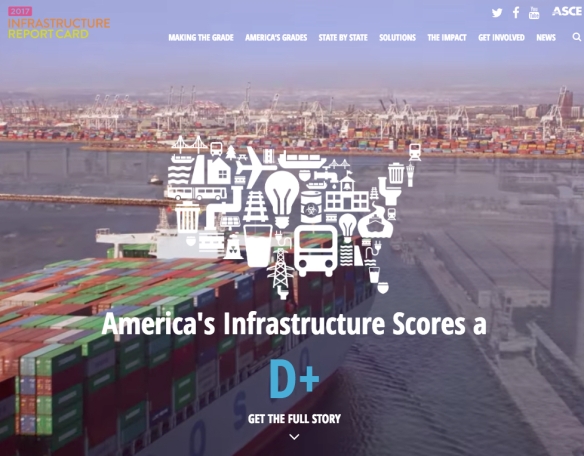

We have written about this previously, the state of American infrastructure and the problem that is not appealing to the masses, and we can report that not a lot has changed. According to ASCE, the US got a 2017 report card for infrastructure and the outcome is pretty static … D+ (same as it has been for the past half-decade or more). Part of that story has to do with the grading system in the first place, but most (near all) has to do with the dwindling state of infrastructure in the past decade of austerity policy that effectively kicks the proverbial can down the road such that the next generation inherits suboptimal infrastructure in the US.

Hong Kong’s “coffin flats” from the Guardian. Take a peek at this story replete with pictures about suffocating housing infrastructure in subdivided flats.

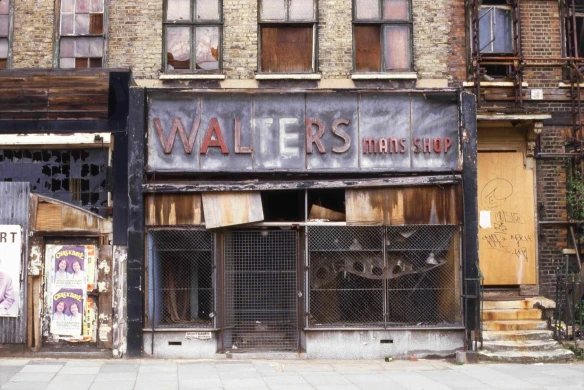

“Ruinphobia” and the anti-ruination reflex — worth a look.

“The problems associated with empty properties are considerable. They attract vandalism and increase insecurity and fear. And this all reduces the value of surrounding businesses and homes. So the decision to leave a property empty is not just a private matter for the landlord. It affects us all.”

Mary Portas, The Portas Review: The Future of Our High Streets, 2011, p 35.

Portas here reveals that any discussion of transience and permanence in urban development engages deeply embedded cultural assumptions about utility and progress. I explore the origins and effects of this anxiety in a contribution to a recently published collection of essays on the theme of temporary re-uses of vacant urban property. In my chapter I show how an underlying ruinphobia quitely but powerfully shapes the fate of abandoned buildings, regardless of how some might more loudly valorise them through a ruinphiliac (or ruin lusty) gaze.

In my chapter I place recent…

View original post 714 more words

https://soundcloud.com/britishacademy/imagining-infrastructures

Fascinating discussion about what infrastructure is and how the concept may have subtly changed over time (for example, the material and conceptual, the blueprint and the waste, etc.). Quality work from the British Academy.

We are living in a time of intellectual fights. As STSers, we sometimes feel like being pushed back into the 1990s, only that the strange debates we had back then on “Science as Practice and Culture” have made it onto the streets and into mainstream media. Sure, we have expressed many times that we love science and love technology and today we join (and even practically and intellectually lead) the “march for science”. But the shortcut “post…” -> “relativism” -> “danger” seems to be still in place. A recent piece on HOW FRENCH “INTELLECTUALS” RUINED THE WEST: POSTMODERNISM AND ITS IMPACT, EXPLAINED argued for that – again. We’ve written about postmodernism many times, even in a 1, 2, 3 set of posts, so there is – intellectually – not a lot to add to that nonsense. But maybe it is time to take that, well, personal again: If that attitude is still a guidance for the modern, for the west, maybe we should have ruined it when we had the chance. Or, if that sounds too offended, why we obviously never had the chance to do so.

With some success, I have been teaching Charles Perrow’s “Normal Accident” concept with “Engineering Disasters.” It is a show on the History Channel, which is itself an offshoot of Modern Marvels). Each show is broken-down into usually four or five vignettes that are essentially “case studies” in engineering accidents and disasters.

These shows can easily be harnessed to walk students through the normal accident concept by analyzing each of the case studies using a worksheet (I could share this with anyone that wants it njr12 at psu.edu) that distills normal accidents into a few component parts. See below. I use Modern Marvels Engineering Disasters 7 in my course and in the image you see the final two cases — Northridge Earthquakes in CA and the Underground Mine Fires in Centralia, PA — and they are cross-referenced with the three criteria that I use from normal accidents, namely,

The students, from what I can gather, enjoy doing this sort of detective work. After four or five case studies, the students typically know how to apply the criteria and, thus, the concept of normal disasters.

Just thought I would mention that I am working on a field-trip project on infrastructure that takes students on a hunt for “signals” of infrastructure in New York based on a book we discussed on the blog a couple years ago. The book is finally for sale, and if you go to the purchasing site, you’ll find a new option to purchase a walking tour that accompanies a copy of the book. It is marvelous.

If you’re on the East Coast, and can get to NYC without a ton of trouble, this is a fascinating look at what the internet infrastructure “looks like,” illustrated with visual examples of what to look for to decode infrastructure cues.

A new piece from The Conversation about security infrastructure investigating security options, including going back to the physical key as an alternative to password overload in online platforms.

“The age of hacking brings a return to the physical key” by Jungwoo Ryoo, Pennsylvania State University

Said it more than a year ago…

Great ANT case for teaching: “New Zealand Grants River Personhood“

Want to take it to the next level in the classroom? challenge students to understand how a person-like “state” (in this case, New Zealand) is apparently accorded the ability to do this!

Ask them, which is weirder, a river being a person or a state granting the personhood?

Introduction: Infrastructural Complications

Penny Harvey, Casper Bruun Jensen & Atsuro Morita

Over the past decade, infrastructures have emerged as compelling sites for qualitative social research. This occurs in a general situation where the race for infrastructural investment has become quite frenzied, as world superpowers compete for the most effective means to circulate energy, goods and money. At the same time, millions of people disenfranchised by trade corridors, securitized production sites, and privatized service provision seek to establish their own possibilities that intersect, disrupt or otherwise engage the high level investments that now routinely re-configure their worlds. The projects of the powerful and the engagements of the poor are thus thoroughly entangled in this contemporary drive to “leverage the future.”

Read the rest here.

A student of mine said something last week that gave me déjà vu. We completed our lessons on “social class” and the student was having difficulty with the notion of cultural capital.

In class, waving an iPhone in the air, s/he said:

“Why would anybody need to know this when you have the whole world’s knowledge in your pocket?”

The student was referring to the ability to command cultural knowledge (i.e., cultural capital).

Reminded me of this immediately: And a student said “Ah, so like, people with cultural capital don’t need Google…ohhhh, I get it”

There is a growing connection between a small research area in the business school literature called “futures studies” (wherein forecasting, scenario planning, etc.) and STS. Early thinkers in (what is now) this area are folks like Toffler; you might remember his books Future Shock or the Third Wave. In the link to STS, foundational thinkers that readers might recall are folks like Cynthia Selin (who I wrote about back in 2011).

Since then, I spent some time reading in “the sociology of the future” and we had a guest that spoke about forecasting (related to weather, Phaedra Daipha), although we have had some other perspectives, namely, some commentary about the future and rubbish.

Well, inspired by this, I started writing with a colleague at Roskilde University (Denmark) named Matthew Spaniol. Our first paper linked STS and futures studies through the notion of multiplicity in “The Future Multiple.” Our new paper, which is nearly out now, deepens this linkage, drawing upon some STS insights to address issues voiced from within futures studies about scenario planning, a process that unfolds, in the standard account, through a series of stages, phases, and steps. We offer a much more tentative understand of that process in “Social Foundations of Scenario Planning.”

In the “Teaching STS” collection, we’ve discussed teaching lessons (with some resources) about the social construction of time a number of times related to whether or not time exists at all (with research from the Max Planck Institute), reflections on the notion of aberrant time such as “leap seconds” (students are bothered by this one), and, even though when we write about the olympics, it is usually about derelict stadiums, it occurs to me that when the atomic clock was adopted and the length of the second transformed, “timing” at the Olympic games might have been an interesting topic to think about for students who imagine that the length of the second back in 1936 should be identical to the length of the second that Michael Phelps was swimming in 2008 (in Beijing).

Source: Teaching STS: Construction of Time and Daylight Savings

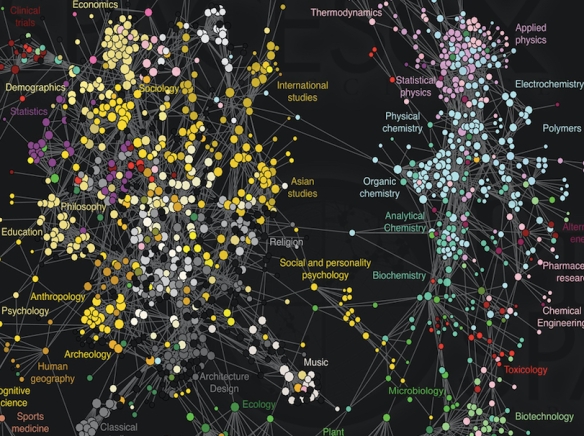

This is cool. Click here for a map of science as we know it. Reminds me of a number of topics we have discussed here, namely, digital methods, maps of submarine cables, and cartographic narratives from the past.

The above image is just a snippet of the original, which is only one of numerous maps to help make sense of massive amounts of data at Places & Spaces, Curated by the Cyberinfrastructure for Network Science Center.

Worth checking-out: visual, psychological, and anthropological films that can be used for teaching from our friends over at Psychocultural Cinema: Despite the rich history of innovative methods and techniqu…

In a fascinating, apparently not-peer-reviewed non-article available free online here, Tommaso Venturini and Bruno Latour discuss the potential of “digital methods” for the contemporary…

Source: Latour on “Digital Methods”

The challenge of de-centering humans — especially in the traditional home of human-centricity like sociology or anthropology but also in the humanities — has been gaining attention for …

Source: When in doubt, de-center humans

You must be logged in to post a comment.