Recently, an old dissertation fell into my lap and I’d like to tell you about it. I asked my work study to find basically anything about the state and state theory for Jan and I’s book “The State Multiple,” which we are writing now. Well, the dissertation was from 1988 by Michael Soupios, now a storied professor at Long Island University here in the states, where he’s being teaching for three decades and more. His 1988 dissertation from Fordham *(he has multiple PhDs) is titled “Human Nature and Machiavelli’s Homeopathic Theory of State” wherein he tackles the basic quandary set forth by Machiavelli.

Quoting the dissertation:

The terms “homopathic” or “homeotherapy” are of medical origin and refer to a form of treatment in which an element similar to the causative agent of a disease is itself used in attempting a cure. It is precisely this approach that we find offered in Machiavelli’s political formula.

The dissertation goes on to explain how Machiavelli’s vision of humans was basically that we are a bunch of decrepit liars and thieves and, thus, deserved to be treated with as much manipulation and self-service as we would impart on others. Call this, let’s say, a Hobbsian antidote to the crisis of the commons and the natural order of man, although Michael Soupios refrains from the comment (good to stay on topic in a dissertation!). We are not to be ruled and governed by a force that helps us to repress our baser instincts and then choose to be together non-violently as a form of supra-self-interest (sort of like a dynamic where we cooperate just long enough to compete, like children playing nearly any game), and, instead, we see Machiavelli’s view that you treat like with like, or his homeopathic view of states. Michael Soupios tackles fear and force, fraud as an instrument of the state, and creative conflict within the state before setting his sights on how this approach could even be instantiated as a model for International Relations.

The dissertation is fascinating and essentially well-written. Now, this view of politics is politics by political means, if you will. Since this writing, STS has entered the discussion of the state, perhaps foremost by my friend and ally in state theory, Patrick Carroll, who, in his many written works, shows how the state, as we know it (i.e., as an actor, a macro entity capable of action, etc.) is a falsehood of sorts and instead the state is made-up of all things stately such as people, bogs, trees, and all the measurement techniques used to make the state’s ‘self’ register in formal documents of statehood and statecraft. For Patrick, the state is constructed and environmental rather than iconic and abstract; material rather than conceptual.

So, with enough force, could Michael Soupios and Patrick Carroll be collided with enough force to make the argument: if one model for the state is homeopathic (i.e., Mach’s), and if one model for the state is material, then could we have a hybrid theory, a homeopathic-material theory of the state?

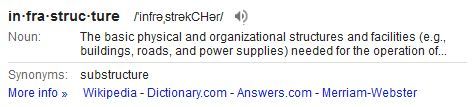

If that is the case: what would the infrastructural equivalent of homeopathic statecraft look like? I don’t yet know, as I’ve only just completed the dissertation read, but it seems like a viable option forward if one wants to engage the cocktail of normative and empirical claims-making that is contemporary political theory.

You must be logged in to post a comment.